- Define a client and server

- Explain what an HTTP request is

- Explain the nature of request and response

- Define a static site vs. a dynamic site

How many times a day do you use the internet? How many times do you load a different web page? Think about how many times you do this in a year! In order to be a developer-- and especially a web developer-- it's incredibly important to understand how the web works. From here on out, you are no longer just a user of the internet. You are a creator of the web.

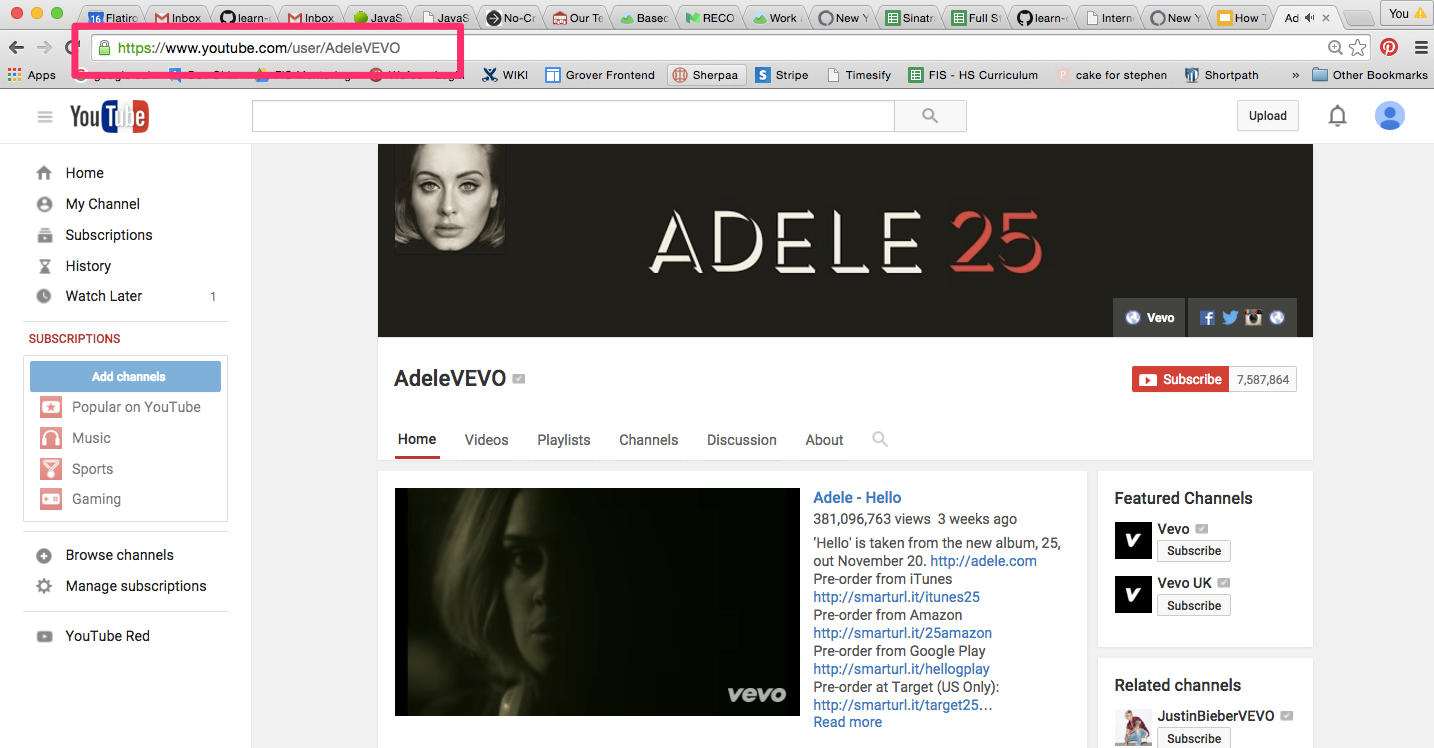

So seriously, how does this:

https://www.youtube.com/user/AdeleVEVO

Turn into this:

The internet operates based on conversations between the client (more familiarly known as the browser) and the server (the code running the web site you're trying to load). By typing in that URL into your browser, you (the client) are requesting a web page. The server then receives the request, processes it, and sends a response. Your browser receives that response and shows it to you. These are the fundamentals of the web. Browsers send requests, and servers send responses. Until today you have always been a client. Moving forward you will be building the server. This means processing requests, creating responses, and sending them back to the client.

We will be writing our servers using Ruby and a few different frameworks. But your browser doesn't know, nor does it care, what server it talks to. How does that work? How can a server that was written 15 years ago still work with a browser written 15 months or days ago?

In addition, you can use multiple clients! You can use Chrome, Safari, Internet Explorer, Opera, and many others. All of those browsers are able to talk to the same server. Let's take a closer look at how this occurs.

Being able to switch out both the server or the client happens because the way browsers and servers talk is controlled by a contract or protocol. Specifically it is a protocol created by Tim Berners-Lee called the Hyper Text Transfer Protocol or HTTP. Your server will receive requests from the browser that follow HTTP. It then responds with an HTTP response that all browsers are able to parse.

HTTP is the language browsers speak. Every time you load a web page, you are

making an HTTP request to the site's server, and the server sends back an

HTTP response.

In the example above, the client is making an HTTP GET request to YouTube's

server. YouTube's server then sends back a response and the client renders the

page in the browser.

When you make a request on the web, how do you know where to send it? This is done through Uniform Resource Identifiers or URIs. You've probably also heard of these as URLs. Both are fine. Let's look at the URI we used up top.

http://www.youtube.com/adelevevo

This URI is broken into three parts:

http- the protocolyoutube.com- the domain/adelevevo- the resource

The protocol is the way we're sending our request. There are several different

types of internet protocols (SMTP for emails, HTTPS for secure requests, FTP for

file transfers). To load a website, we use HTTP.

The domain name is a string of characters that identifies the unique location

of the web server that hosts that particular website. This will be things like

youtube.com and google.com.

The resource is the particular part of the website we want to load. YouTube

has millions and millions of channels and videos, so the specific resource we

want is /adelevevo (because we can't get Hello out of our heads).

An analogy that works well is thinking of an apartment building. The domain is

the entire building. Within that building though there are hundreds of

apartments. We use the specific resource (or sometimes called path) to figure

out that we care about apartment 4E. The numbering/lettering system is different

for every apartment building, just like how a server has its resources laid out

is a bit different for every website. For example doing a search on Google ends

in a URL like this https://www.google.com/search?q=URI but searching for URI

on Facebook leads to this URL https://www.facebook.com/search/top/?q=uri.

When you're making a request, not only do you want to give all the details of

your request, you also need to specify what action you would like the server to

do. We do this with HTTP Verbs. With the same resource, you may want more than

one action to occur. Using a browser, almost all requests are GET requests.

This just means "hey server, please GET me this resource". There are a few other

verbs though. What if we want to send some data from the user to the server?

This is done with a POST request. There are a ton of verbs, and we'll go

further into them later, but here is a full list:

| VERB | Description |

|---|---|

| HEAD | Asks for a response like a GET but without the body |

| GET | Retrieves a representation of a resource |

| POST | Submits data to be processed in the body of the request |

| PUT | Uploads a representation of a resource in the body of the request |

| DELETE | Deletes a specific resource |

| TRACE | Echoes back the received request |

| OPTIONS | Returns the HTTP methods the server supports |

| CONNECT | Converts the request to a TCP/IP tunnel (generally for SSL) |

| PATCH | Apply a partial modification of a resource |

Our client so far has made a request to YouTube's server. In this case, a

request to /adelevevo. The server then responds with all the code associated

with that resource <!doctype html> .....</html>, including all images, CSS

files, JavaScript files, videos, music, etc.

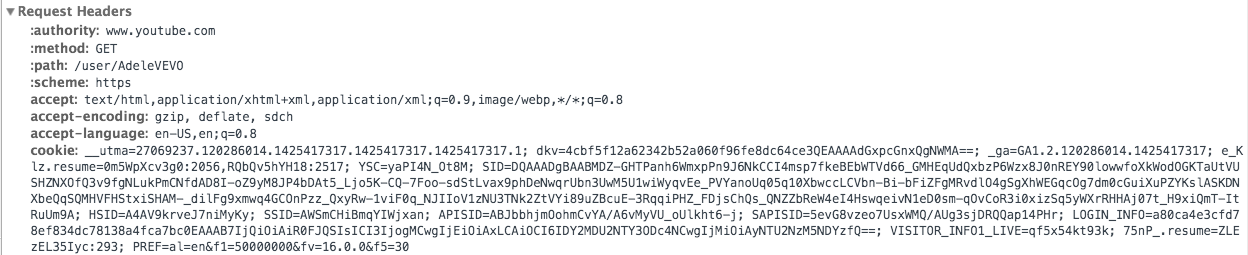

When the client makes a request, it includes other items besides just the URL in the "headers." The request header contains all the information the server needs in order to fulfill the request: the type of request, the resource (path), the domain as well as some other metadata like what type of browser is making this request. The request header would look something like this.

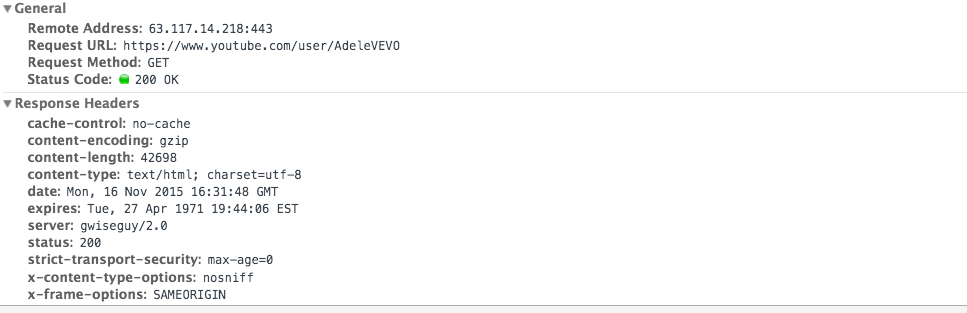

Once your server receives the request, it will do some processing (run code you wrote!) and then send a response back. The server's response headers look something like this:

The server's response is separated into two sections, the headers and the body. The headers are all of the metadata about the response. This includes things like content-length (how big is my response) and what type of content it is. The headers also include the status code of the response. The body of the response is what you see rendered on the page. It is all of that HTML/CSS that you see! Most of the data of a response is in the body, not in the headers.

Every time there is a successful response (you'll know it's successful because

the page will load without any errors), it's a status code of 200, but there

are other status codes and it's good to get familiar with them. You've probably

seen the second most popular status code, 404. This means "file not found."

Status codes are separated into categories based on their first digit. Here are

the different categories:

- 100's - informational

- 200's - success

- 300's - redirect

- 400's - error

- 500's - server error

A full list of status codes is up on Wikipedia.

It's important to note that there are two different types of webapps: static and

dynamic. A static webapp is one that doesn't change. The content doesn't

change unless a developer opens up an HTML file and modifies the content of that

file. Dynamic webapps are sites where the content changes based on user input

(e.g. Facebook, Twitter, Yelp, etc.). Every time you visit the site, the content

is most likely different because someone else gave a review of that restaurant,

or sent out a new tweet, or commented on that image you liked. These are the

types of apps you'll be building.

The flow of request and response changes slightly based on a static or a dynamic webapp.

When the client wants to load a static site, the client makes a request, the server finds the file on a disk, and sends it back. Done and Done.

It gets a little bit more complex with a webapp. The client makes a request, the server runs application code (think of this as your Ruby code), and returns a dynamically generated response.